The Biology of Prenatal Development Student Study Guide

The Biology of Prenatal Development Student Study Guide is a two-sided, fold-out, poster quality study guide for educators to use in their classrooms. The study guide features stunning prenatal imagery depicting the entire prenatal development process, prenatal facts, and a prenatal development timeline that continues from front to back. It is best used as a companion to The Biology of Prenatal Development DVD.

Study Guide Script

Fertilization marks the onset of human development.1 When a man’s sperm enters a woman’s oocyte, the resulting one-cell embryo is called a zygote.2 HCG confirms pregnancy by 8 days.3Between 6 and 12 days, the maturing blastocyst embeds into the inner wall of the mother’s uterus.4 Soon after, the placenta and then the umbilical cord begin to grow.5

The neural plate emerges by 2 weeks, 4 days.6 By 3 weeks the neural tube appears, marking the onset of brain and spinal cord development.7 Blood cells and blood vessels also form.8 By 3 weeks, 1 day the heart begins to beat in the newly forming circulatory system.9

The cerebellum is developing by 4 weeks10 and by 4½ weeks the cerebral hemispheres appear.11 Brainwaves have been recorded at 6 weeks, 2 days.12

Movement begins by 5½ to 6 weeks.13 The embryo first moves the head and twists the trunk.14 Such movement is essential for normal development of bones and joints.15

Fingers begin to separate in the 6½-week embryo16 and are completely free by 7½ weeks,17 at which time the hands can touch.18 Handedness is evident by 8 weeks, when 75% of embryos exhibit right-hand dominance.19

At the end of the embryonic period, the embryo possesses more than 90% of the structures found in the adult.20 The embyro’s heart now has 4 chambers21 and beats about 170 times per minute.22

The fetus swallows by 9 weeks23 and sucks the thumb,24 usually favoring the right thumb.25 At 10 weeks fingernails and toenails are growing26 and fingerprints form.27

By 9 weeks the face, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet can sense light touch.28 Most of the fetus is touch-sensitive by 13 to 14 weeks.29 Gender differences emerge as female fetuses move their jaws more than males.30

By 9 weeks the face, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet can sense light touch.28 Most of the fetus is touch-sensitive by 13 to 14 weeks.29 Gender differences emerge as female fetuses move their jaws more than males.30

By 14 weeks a fetus touched near the mouth shows the same rooting reflex newborns use to find their mother’s nipple when breastfeeding.31

Pregnant women first feel the fetus move between 14 and 18 weeks.32 This event is called quickening.33

Around 19 weeks; movement, breathing, and heart rate begin to follow daily cycles called circadian rhythms.34 These biologic rhythms persist throughout childhood and adulthood.

By 20 weeks the cochlea, which is the organ of hearing, reaches adult size within the fully developed inner ear.35 From now on the fetus hears and responds to a growing medley of sounds.36

Rapid Eye Movements (REM) are first seen in the 20-week fetus.37 After birth, REM are known to occur during the dream stage of sleep.38 By 23 weeks all skin layers and structures including glands and hair follicles are present.39

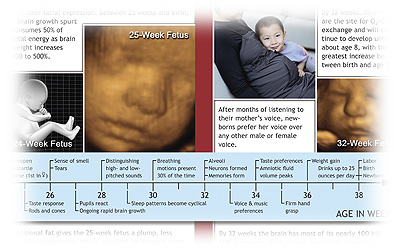

By 25 weeks the fetus responds to taste. Sweet substances placed in the amniotic fluid increase fetal swallowing. Bitter substances decrease swallowing and may alter facial expression.40 Between 25 weeks and birth, a brain growth spurt consumes 50% of fetal energy as brain weight increases 400 to 500%.41

Additional fat gives the 25-week fetus a plump, less wrinkled appearance.42 Newly acquired fat deposits store energy and help maintain body temperature after birth.43

By 24 weeks the eyelids reopen.44 By 25 weeks, highly developed eyes contain rods and cones.45 A total of 200 million rods will detect low levels of light as 14 million cones produce focused, color images.46 Eyes form tears by 26 weeks.47 By 27 weeks, pupils dilate and constrict in response to light — a reflex that persists throughout life.48

By 24 weeks the eyelids reopen.44 By 25 weeks, highly developed eyes contain rods and cones.45 A total of 200 million rods will detect low levels of light as 14 million cones produce focused, color images.46 Eyes form tears by 26 weeks.47 By 27 weeks, pupils dilate and constrict in response to light — a reflex that persists throughout life.48

True alveoli, or air “pocket” cells, begin forming in the lungs by 32 weeks. Alveoli are the site for O2/CO2 exchange and will continue to develop until about age 8, with the greatest increase between birth and age 2.49

After months of listening to their mother’s voice, newborns prefer her voice over any other male or female voice.50

By 32 weeks the brain has most of its nearly 100 billion (1011) neurons.51 Each neuron eventually connects with up to 200,000 other neurons, creating an electrical network of incalculable complexity.52 These connections are called synapses.53 At birth most organs are just 5% of their adult size. However, the newborn’s brain and eyes are approximately 25%54 and 75%55 of their final sizes respectively.

Newborns show a preference for prose passages and lullabies heard during the last 6 weeks of pregnancy. These preferences for familiar experiences provide evidence of memory formation and learning before birth.56

Endnotes

Bibliography: www.ehd.org/science_brochure.php

Detailed Development Timeline: www.ehd.org/timeline.php

Photo Credits: (left to right, top to bottom) Cover: EHD/The Biology of Prenatal Development (BPD) Video; LifeArt/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Getty Images (next 3); 0-4 Week Panel: Lennart Nilsson/Albert Bonniers Forlag AB, A Child Is Born, Dell Publishing Company; Centro Riproduzione Assistia (next 7); LifeArt (next 2); EHD/BPD. 4-8 Week Panel: EHD/BPD; Nilsson/Forlag (next 3); EHD/BPD. 8-16 Week Panel: EHD/BPD; Getty Images (next 2); Nilsson/Forlag. 16-24 Week Panel: Nilsson/Forlag; LifeArt; Getty Images; Nilsson/Forlag (next 2). 24-32 Week Panel: EHD/BPD; Create Health Centre for Reproduction and Advanced Technology; Nilsson/Forlag. 32-38 Week Panel: Getty Images; Create Health Centre; Getty Images (next 3). Back: Getty Images (all 5).

All images are copyrighted and reproduced with permission.

This study guide is licensed to schools for use by educators and students only. May not be reproduced, resold, or redistributed without the express written consent of The Endowment for Human Development, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2005 by The Endowment for Human Development, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Footnotes